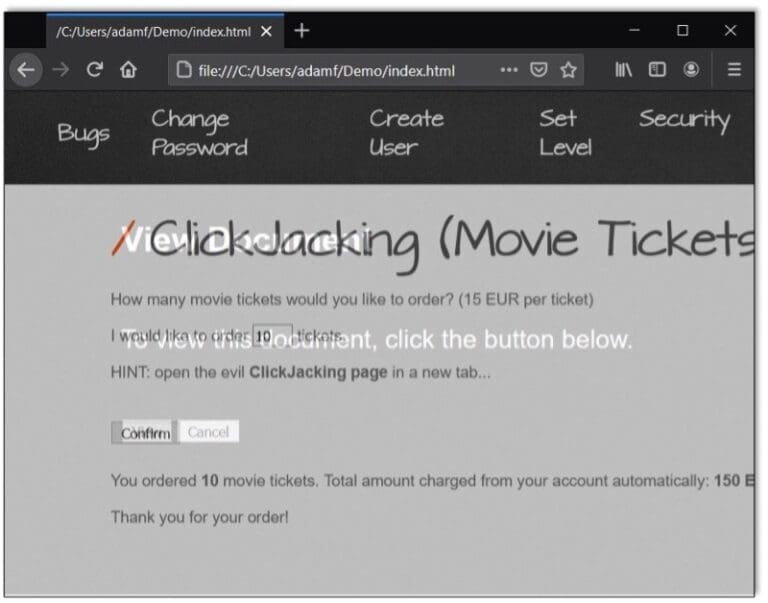

Realistically Assessing the Threat of Clickjacking Today: A Penetration Tester Perspective

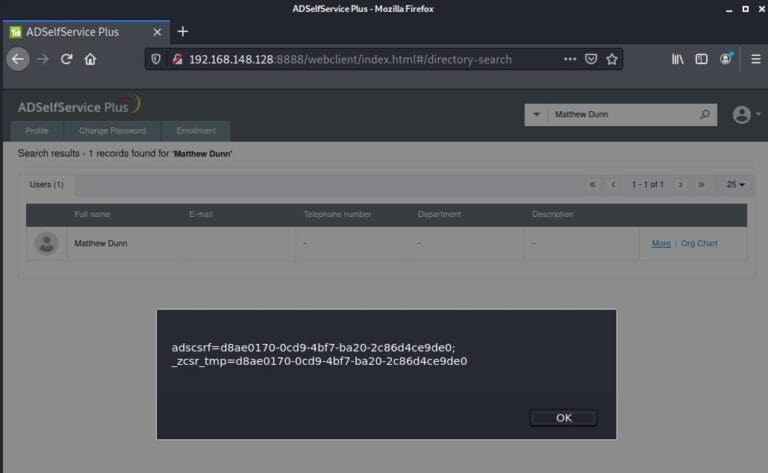

Raxis’ Lead Developer Adam Fernandez discusses clickjacking, explaining what it is and why it represents less of a threat now than it once did. Adam also talks about how clickjacking differs from similar attacks.