Lateral Movement: From Beachhead to Breach

When a network gets compromised, often the initial foothold gained is far removed from the attacker’s real goal. Sensitive information may be secreted away deep inside the network – and, even when it isn’t, the compromised system itself still might not have whatever an attacker is looking for.

During the early stages of a breach, the goal isn’t necessarily to secure the loot so much as it is establish a beachhead: building a pool of compromised resources the attacker can use to levy further attacks within the network. This process of pivoting through compromised resources is called lateral movement – and it’s how minor breaches, like a compromised fish tank thermostat at a casino, escalate into critical security incidents.

In today’s blog, we’ll look into how we use lateral movement on internal network penetration tests and red team engagements, and I’ll discuss some of the tools I find most useful in these attacks.

Lateral Movement Basics

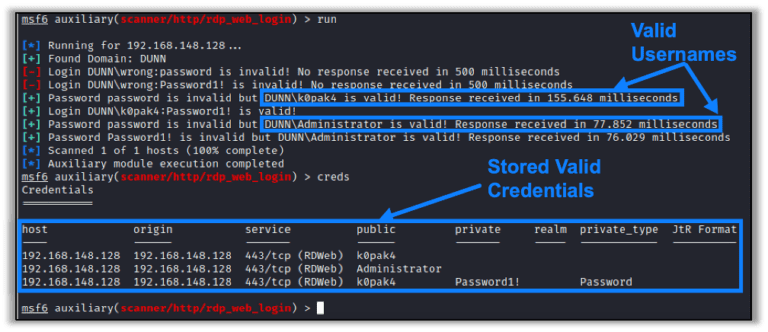

Lateral movement isn’t any one particular technique but rather an umbrella term for using the access at one’s disposal to compromise other resources. At its most basic, lateral movement can be as simple as recycling discovered credentials to log into other devices on the network or using a compromised domain administrator account to push downloaded malware onto computers managed by the compromised domain.

In other cases, lateral movement can involve deploying network proxies on compromised systems to gain visibility into closed networks, tampering with internal webpages to inject malicious JavaScript into visiting browsers, or even abusing group policy permissions to take over other accounts.

In many cases, one can achieve lateral movement without uploading malware or specialized tools to the compromised devices, simply by reusing resources already available for legitimate reasons. A stolen SSH key is not only more reliable than an exploit for SSH but also blends in with normal network activity, making it less likely to be detected. SSH also comes with built-in options for quickly deploying network proxies, bypassing the need for pivoting tools like Chisel and further reducing an attacker’s network signature.

Lateral movement doesn’t always have to live off the land, however. By deploying tools like Chisel or Ligolo-ng, an attacker can use a compromised system to explore the network it belongs to or extract hashed credentials with tools like Mimikatz for offline brute-force or pass-the-hash attacks.

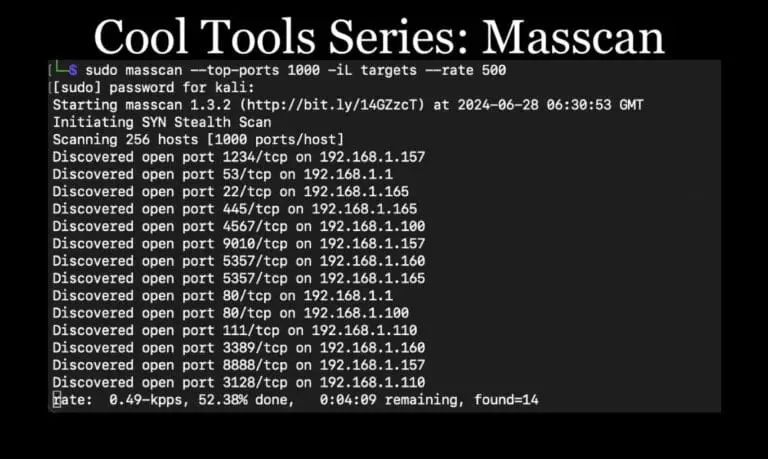

Alternatively, merely having this new vantage point can allow an attacker to enumerate and exploit internal systems that aren’t normally reachable from outside the network. Put together, this means that, instead of relying on weak passwords or outdated software, an attacker can string together normal accounts, devices, and configurations to move around the network, gathering more and more resources as they go.

Tools of the Trade

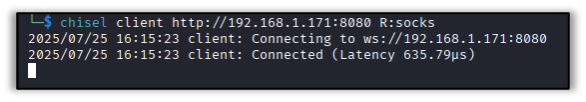

Chisel

Chisel is a tunnel creator that can be deployed on a compromised server to route network traffic from an attacker through the compromised system. It’s not the only one – I personally have had good experiences with Ligolo-ng – but it’s also one of the most widely-used tool sets. For the stealth-inclined, one can forgo specialized software entirely and use native software like SSH to establish SOCKS proxies or even configure a VPN connection with WireGuard to build pathways into the network. Regardless of method, the end result is the ability to route traffic to normally inaccessible systems. This expanded posture can then be combined with conventional techniques to further enumerate and access whatever new networks are encountered.

Mimikatz

In the realm of post-exploitation, Mimikatz probably occupies a special space in your toolbox already, but, in a networked environment, it can do a great deal more than harvest password hashes. Once deployed, Mimikatz can pull cleartext credentials from memory, hijack recently used domain accounts, and even help provision golden tickets that can authorize access to any domain resource. Of course, Mimikatz isn’t the only tool with these capabilities, but it’s incredibly handy for a wide variety of credential-stealing scenarios.

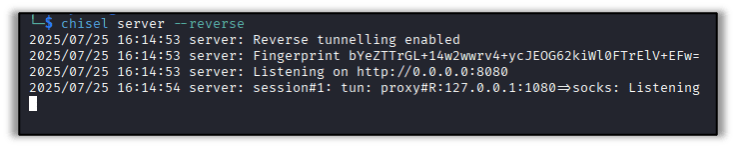

Bloodhound

Bloodhound is arguably one of the most famous lateral movement tools. It differs from others because it’s not designed for exploitation at all – instead it enumerates Active Directory domains, searches for users, groups, and devices, and – most importantly – enumerates the relationships between them.

For instance, if [email protected] is an administrator and anyone in IT can change jdoe’s password, then all one has to do to become an administrator is to join the Active Directory group for IT. If anyone in management can change group memberships, then compromising a manager is as good as compromising an administrator. And, if there’s a misconfiguration that allows any service account to make arbitrary modifications to a management user, then control of the domain is an MS-SQL query or two away.

Bloodhound is designed to search for these paths to turn the access one has into the access one wants, even wandering across multiple connected domains if necessary.

No Tool at All

In pentesting, sometimes the exploit isn’t a piece of software or a careful procedure but, instead, simply making use of access one already has. This, like all lateral movement – and pentesting in general – is dependent on the environment.

Find an internal blog that lets you insert PHP code? A single line PHP backdoor can turn a wiki into a weapon.

Obtain the SSH private key for Ansible? You can log into everything it can – or why not make a custom playbook to run your backdoor automatically instead?

Have a backdoor on one of several linked MSSQL servers? Crafting queries to run shell commands on the other linked servers can be done right from the native SQL console.

Tools are useful for many lateral movement purposes, but often more access can be obtained – and with less effort and detectable signatures – simply by asking nicely.

This last approach means lateral movement vectors can be tricky to spot – a somewhat permissive GPO here, a recycled password there, and a perfectly reasonable configuration over there – can be chained together to infiltrate otherwise well-protected networks, plant backdoors in plain sight, and turn the networks own configuration against itself.

Lateral Movement Defenses

With the varied forms of lateral movement available to attackers, preventing lateral movement requires equally broad countermeasures. A few recommendations:

- Defense in Depth: Just like there is no single way to hack a network, neither is there is a magic bullet to defend one. Stacking multiple defensive measures covers blind spots and minimizes attack surfaces, cutting off attackers at every turn.

- Least Privilege: Like the name implies, the Principle of Least Privilege states that each resource on the network should be granted only the access it strictly needs, and no more. If fewer accounts or computers can do certain things, then any attacker needing to exploit a vulnerability must contend with a smaller pool of targets – and can be funneled towards specific paths that are well defended.

- Network Segmentation: Related to the Principle of Least Privilege, network segmentation limits the devices an attacker can interact with, further restricting their options.

- Intrusion Detection: There is a variety of intrusion detection and protection (IDS/IPS) software designed to scrutinize network traffic and device activity for suspect behavior, providing a single pane of glass to identify potential risks to operational stability. By figuratively stringing tripwires throughout one’s environment, one can detect when an attacker might be snooping, and even quarantine suspect systems to isolated network segments, mitigating risk proactively.

- Regular Penetration Tests: No matter how robust network security controls become, organizations would be well served to test defenses in regular live fire exercises. A pentest can simulate specific threat models, such as a compromised account, disgruntled insider, or infected device, and can search for lateral movement pathways that would otherwise elude scanning tools.

Wrapping Up

Thanks for reading. Whether you’re a member of a blue team, specialized IT group, or someone seeking a vocation in adversarial security practices, I hope this blog has helped elucidate the nuance and complexities of manual penetration testing techniques.

If you found this interesting, I hope you’ll check out Andrew Trexler’s Active Directory series as well.